Market watch

Five macro themes to watch in 2025

Issue date: 2025-01-24

abrdn

We consider five themes for 2025, including slowing monetary policy easing, rising fiscal sustainability concerns, winners and losers from the changing patterns of globalisation, and major sources of political and geopolitical risk.

Key Takeaways

- The rate cutting cycle is getting cut short, at least in the US and some EMs.

- Debt is a worry again, and the term premium is likely to rise further.

- There can be emerging market winners as well as losers from changing patterns of globalisation.

- Any ceasefire in Ukraine or the Middle East will be unstable.

- Europe is the next locus of political risk.

The rate cutting cycle is getting cut short

We expect the Federal Reserve (Fed) to cut to a higher terminal rate, following the Republican sweep in the US election.

Specifically, we now see the rate cutting cycle stalling at a fed funds rate of 3.5-3.75% in the second half of 2025, 75bps higher than our pre-election expectations.

This is in part driven by stronger short-term growth. While the exact contours of the policy agenda under a second Donald Trump term remain opaque, we expect a combination of fiscal loosening and deregulation to modestly lift growth, albeit with most of the boost coming in 2026 when any extra tax cuts would take effect. This pickup in demand will contribute to stronger inflationary pressures.

Other aspects of Trump’s agenda will also put upward pressure on prices via a negative supply shock. These include large tariff increases on imports from China and targeted increases on some other trade partners or product groups, as well as a sharp decline in net migration, which has been an important driver of the easing of the labour market in recent years.

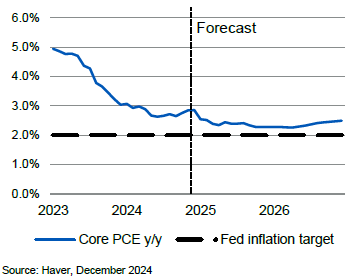

As a result of these shifts in aggregate demand and supply, we think the Fed’s preferred measure of core PCE inflation will get stuck at close to 2.5% year over year through 2025 and 2026 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: We now forecast US core PCE inflation to get stuck above 2% for a period of time

This means the Fed will have less room to ease policy. We think it will need to keep interest rates well above neutral to keep inflation expectations anchored. Trump’s policy changes could also put some modest upward pressure on equilibrium interest rates themselves via larger fiscal deficits or stronger private investment.

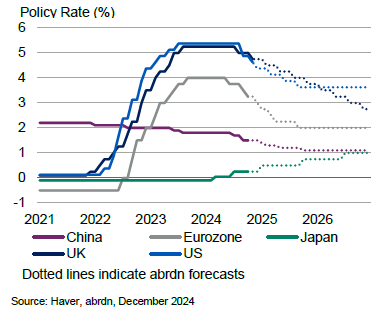

A higher-for-longer profile for US rates will affect central banks across the world in different ways (see Figure 2). 0.0% 1.0% 2.0% 3.0% 4.0% 5.0% 6.0%2023 2024 2025 2026 Core PCE y/y Fed inflation target

In general, the direction of travel for emerging markets (EMs) remains for lower rates, but the pace and extent of their cutting cycles might be more restrained.

By contrast, the spillover effects from Trump’s trade policy agenda will add to Eurozone growth concerns, encouraging a slightly deeper easing cycle.

Finally, more of the work supporting the yen via closing US-Japan rate differentials will now fall on the BoJ, which may encourage more rapid hiking in coming years.

Figure 2: We expect a higher terminal rate in the US, further easing in Europe, additional stimulus from China, and gradual hikes in Japan

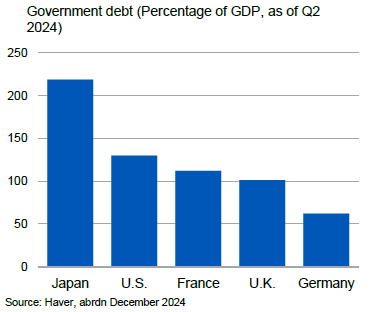

Debt is a worry again

Global government debt has risen above $100 trillion, close to 100% of global GDP (see Figure 3). US government debt is well over 100% of GDP and the deficit is 6.7%. This is extremely large given that the economy is essentially at full employment.

Figure 3: Debt to GDP ratios are very elevated in many economies

Depending on quite what he does, Trump’s policies could increase the US debt and deficit even further. In our base case, we see the deficit increasing to above 7% of GDP, and there are scenarios in which it climbs much more.

Fiscal sustainability doesn’t turn on any particular level of debt or deficit. Instead, it depends on the relationship between the real growth rate of the economy (g) and the real interest rate paid on debt (r). If r exceeds g, then the debt stock increases without bound unless fiscal policy runs a primary surplus.

Because the US dollar is the global reserve currency, r is lower in the US than it might be in other countries which tried to run similar economic policies. US government securities are in high demand as a place to store value, meaning the price of US assets is higher and interest rates lower than they otherwise would be.

The dollar’s status as a reserve currency is the result of very deep and liquid US capital markets, and powerful network effects. But it also relies on perceptions of US rule of law and institutional stability.

So, it is possible that if Trump pursues policies that are perceived as weakening US institutional credibility, especially around the Fed, this could threaten the dollar’s standing as a reserve currency.

Given the lack of alternatives to the US dollar, and the appointment of broadly “institutional” policymakers to key economic positions in the incoming administration, this extreme outcome seems unlikely.

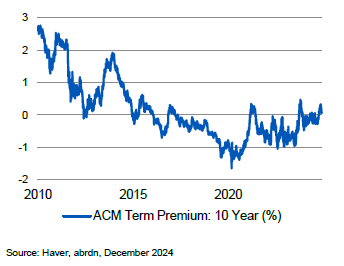

However, Trump’s fiscal policy may still lead to higher term premia on US debt (see Figure 4). Increased Treasury supply may require the price to fall to clear the market. And investors may demand more compensation for the risks of higher inflation and greater uncertainty associated with the Trump presidency.

Moreover, we think the term premium may also increase for non-debt related reasons. More negative supply shocks, such as from climate change and geopolitics, will lead to more periods of high inflation and low growth. This may cause sustained positive correlation between bonds and equities, pushing up on the term premium and so US borrowing costs.

Figure 4: The US term premium has been increasing, but could rise further

There can be emerging market winners as well as losers from changing patterns of globalisation

Heightened trade policy uncertainty and a more inflationary backdrop in the US will be difficult for many EMs to navigate. But there can be winners as well as losers in 2025 and beyond.

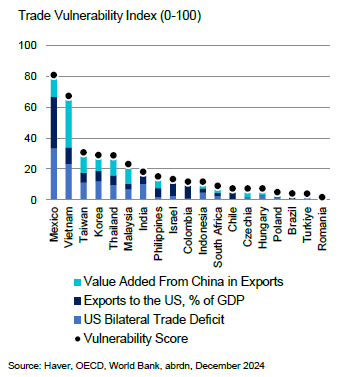

Aside from China, Mexico’s and Vietnam’s large trade surpluses with the US put them at the greatest risk of punitive action from Washington (see Figure 5). They, among other EMs in APAC, depend the most on exporting to the US, while also utilising substantial inputs from China.

Figure 5: Outside of China, Mexico and Vietnam are the most vulnerable to shifting US trade policy

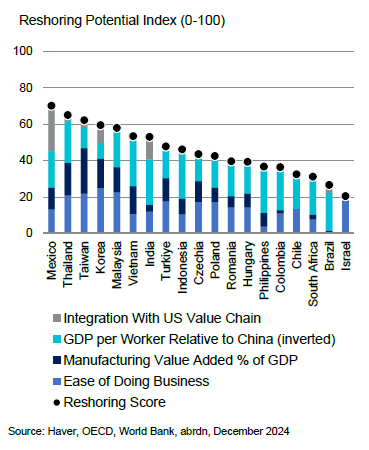

That said, while these vulnerabilities are reasons to expect bouts of market pressure, many of the same EMs are likely to emerge as the long-run winners of shifting supply chains, especially if US efforts primarily focus on decoupling from China (see Figure 6).

For example, in our modelling work, Mexico ranks as the most vulnerable to US trade measures but also the biggest potential reshoring winner.

We think that US tariff threats against Mexico and talks of ripping up the United States-Mexico-Canada free trade agreement (USMCA), are a means of pressuring Mexico to stem migration and raise border security with the US.

As such, we do not anticipate a breakdown of the US-Mexico trading relationship. Mexico’s deep integration with US manufacturing underpins our view that it will ultimately be spared from major trade restrictions, as was the case during Trump’s first presidency.

Indeed, the more the US decouples from China, the more it will need other countries, and Mexico is well placed to capture this change.

Away from trade, a slower pace of Fed easing will complicate monetary policy decisions for the more Fed-sensitive EMs (e.g. Mexico, Indonesia) and potentially add to FX pressures in those markets where fiscal policy and debt concerns are highest (e.g. Brazil).

Figure 6: But many of the most vulnerable economies also have the most to gain from reshoring trends

Any ceasefire in Ukraine or the Middle East will be unstable

US foreign policy will try to create the conditions for ceasefires in both Ukraine and the Middle East.

On Ukraine, the incoming Trump team appears divided over whether the way to achieve a ceasefire is via an increase or a decrease in Ukrainian aid in the short term.

There is also a significant possibility talks do not begin at all, or fall apart rapidly, given Russian momentum on the battlefield and Ukrainian opposition to formalising territorial losses.

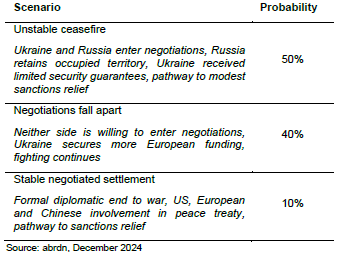

Nevertheless, our base case is now for a ceasefire agreement (see Figure 7), even if this is very likely to be fragile. We envisage this involving Russia retaining occupied territory, Ukraine receiving limited security guarantees which fall well short of a path to NATO membership, and a pathway to modestly ease Russian sanctions.

Europe will be under pressure to increase its share of aid for Ukraine, putting upward pressure on defence budgets at a time of fiscal consolidation across the bloc.

Figure 7: A stable, negotiated settlement to the Russia- Ukraine war remains very unlikely

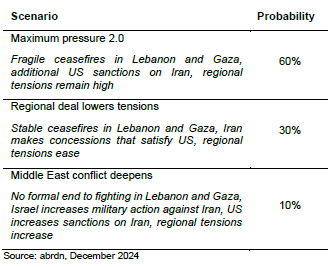

We also expect ongoing volatility in the Middle East, even as Israel reduces the scope of combat operations in Gaza and Lebanon (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: The Trump administration will turn its Middle East focus towards Iran

For a start, any ceasefire will be extremely fragile and easily broken.

More fundamentally, we expect the focus of Israeli and US security policy to increasingly focus on Iran.

The incoming US administration will likely be supportive of Israel’s efforts to restore deterrence. Our base case envisages intermittent military exchanges between Israel, Iranian-backed militia groups, and Iran itself.

We also expect US policy towards Iran to return to a similar position to the one it was in under Trump’s first term (“maximum pressure”), with a greater use and enforcement of sanctions (including on oil exports) and constraining the Iranian nuclear programme.

While there is an upside scenario in which Iran responds to US pressure by ending its nuclear programme and regional tensions improve significantly, there is also a downside one in which direct Israeli-Iranian fighting escalates into a larger regional war.

Europe is the next locus of political risk

Following the collapse of the “traffic-light” coalition, German federal elections are likely to occur in the spring.

A key electoral issue is the future of the “debt brake”, which limits deficit spending to 0.35% of GDP. The rule has come in for criticism as Germany grapples with a significant public investment shortfall, economic stagnation, and increased pressure on defence and climate spending.

Left-wing parties, including current Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s SDP and the Greens, are in favour of relaxing these rules. And Friedrich Merz, who would become chancellor if the CDU/CSU coalition wins, has expressed openness to reform.

We think Germany’s next government will reform the debt brake in some capacity, but the contours of any changes are much less certain.

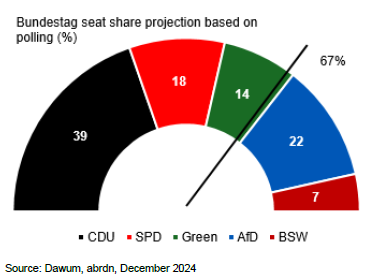

Much depends on the eventual government’s seat count. A two-thirds majority of the Bundestag is required to pass constitutional amendments to the debt brake. Some polls suggest a grand coalition of the CDU, SPD, and Greens might be able to achieve this (see Figure 9). This could see the limit on deficit spending increased, or a permanent exemption to the debt brake for infrastructure spending made.

Figure 9: A “Kenya” coalition might have enough seats in the Bundestag to reform the debt brake

Without a supermajority, the government could still legislate for a temporary triggering of the “escape clause”. However, Scholz’s attempts to use this method ran into legal frustration previously.

Either way, any reform of the debt brake is likely to translate to only modest fiscal expansion for several reasons.

First, some proposed reforms to the debt brake would require Germany to reduce debt/GDP to 60% before it can employ additional fiscal headroom. Second, EU fiscal rules will continue to bind, and these also require Germany to reduce its debt ratio to 60%. Third, support in the CDU and the electorate for debt brake reform is lukewarm at best, making incremental change more likely.

Meanwhile, France’s political and fiscal problems are more acute.

The failure of Michel Barnier’s minority government to pass a budget containing the fiscal consolidation required by the European Commission’s Excessive Deficit Procedure leaves France in a deep political hole.

Fresh parliamentary elections are only possible one year after the previous election, meaning that Emmanuel Macron’s presidency will need to hobble along until the summer before a new parliamentary vote can be called. It is far from clear how a government can be formed in the meantime that will retain parliamentary confidence.

So France’s precarious fiscal position continues to look very challenging, and we think the country should be seen more as a peripheral market than a core one, and French spreads should trade accordingly.

| Important Information For professional and Institutional Investors only – not to be further circulated. In Switzerland for qualified investors only. Any data contained herein which is attributed to a third party (“Third Party Data”) is the property of (a) third party supplier(s) (the “Owner”) and is licensed for use by abrdn**. Third Party Data may not be copied or distributed. Third Party Data is provided “as is” and is not warranted to be accurate, complete or timely. To the extent permitted by applicable law, none of the Owner, abrdn** or any other third party (including any third party involved in providing and/or compiling Third Party Data) shall have any liability for Third Party Data or for any use made of Third Party Data. Neither the Owner nor any other third party sponsors, endorses or promotes any fund or product to which Third Party Data relates. **abrdn means the relevant member of abrdn group, being abrdn plc together with its subsidiaries, subsidiary undertakings and associated companies (whether direct or indirect) from time to time. The information contained herein is intended to be of general interest only and does not constitute legal or tax advice. abrdn does not warrant the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of the information and materials contained in this document and expressly disclaims liability for errors or omissions in such information and materials. abrdn reserves the right to make changes and corrections to its opinions expressed in this document at any time, without notice. Some of the information in this document may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events or future financial performance of countries, markets or companies. These statements are only predictions and actual events or results may differ materially. The reader must make his/her own assessment of the relevance, accuracy and adequacy of the information contained in this document, and make such independent investigations as he/she may consider necessary or appropriate for the purpose of such assessment. Any opinion or estimate contained in this document is made on a general basis and is not to be relied on by the reader as advice. Neither abrdn nor any of its agents have given any consideration to nor have they made any investigation of the investment objectives, financial situation or particular need of the reader, any specific person or group of persons. Accordingly, no warranty whatsoever is given and no liability whatsoever is accepted for any loss arising whether directly or indirectly as a result of the reader, any person or group of persons acting on any information, opinion or estimate contained in this document. This communication constitutes marketing, and is available in the following countries/regions and issued by the respective abrdn group members detailed below. abrdn group comprises abrdn plc and its subsidiaries: abrdn Hong Kong Limited. This material has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission. © 2025 abrdn |