Market watch

How do US tariffs change the global economic outlook?

Issue date: 2025-04-16

Aberdeen Investments

Specifically, the US will impose a minimum universal tariff of 10% on most trade partners, and higher reciprocal tariffs on roughly 60 trading partners based on their trade deficits with the US. We estimate that the US average tariff rate will increase to 22% given these measures. This is above 1930s highs and last reached in the early 1900s.

While there may be scope for this to come down over time as deals are done with trade partners, it’s also possible that the tariff level keeps moving higher in the near term as retaliation occurs and more sector-specific tariffs are introduced. Pending further modelling, we think the full increase in US tariffs so far in Trump’s term could add 2% to the US price level and push GDP down by 1-2%. This would leave the US economy flirting with a recession.

Beyond the US, while there are no winners from this trade war, a relative spectrum has emerged. Canada and Mexico appear to get off lightly, China and Asian economies are heavily impacted, and Europe sits somewhere in the middle, with the UK facing a lower rate than the EU. Nevertheless, the tariffs will be a negative growth shock for the global economy.

Higher, broader tariff increases than expected

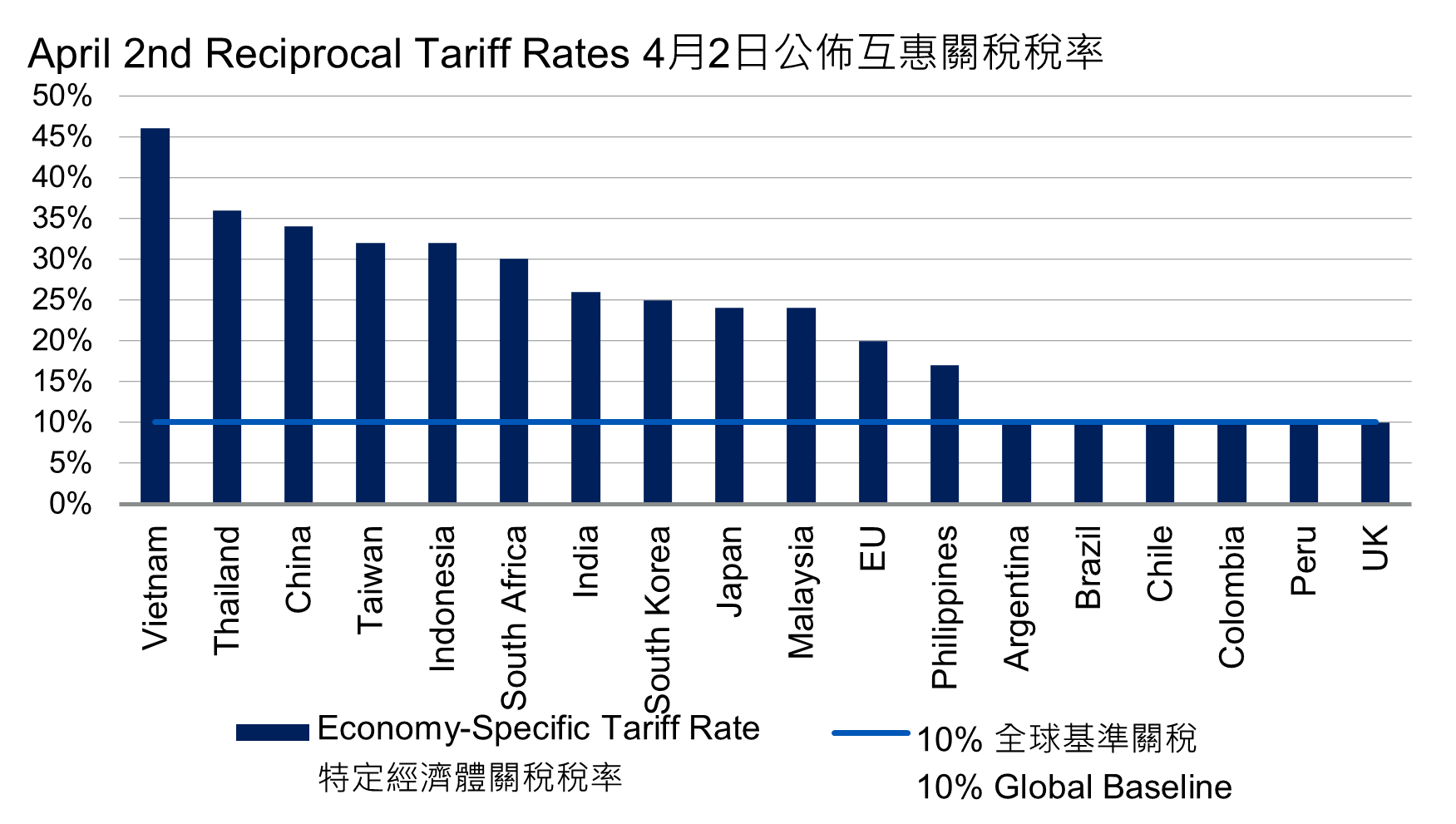

US President Donald Trump has announced a reciprocal tariff regime that exceeds our base case expectations and, based on the price action, those of financial markets. Specifically, the US will impose a minimum universal tariff of 10% on all trade partners (excluding Mexico and Canada) from 5 April, and higher reciprocal tariffs on roughly 60 economies from 9 April (see Figure).

Figure: The 10% global baseline is a floor on tariff rates, with higher rates for economies with which the US runs trade deficits

The administration has focused on trade deficits as the backbone of the reciprocal tariff calculation, rather than attempting a highly complex market-by-market assessment of product-level tariffs and non-tariff barriers. Instead, the reciprocal tariff is calculated by dividing each market’s trade surplus with the US by its total exports. This number, described by the Trump administration as the “tariff charged to the US” by each trade partner, is then roughly halved (what Trump called “kind reciprocal”), resulting in the rate applied by the US.

While there are no winners from this trade war, a relative spectrum has emerged.

Canada and Mexico were notable for their absence from the ‘tariff board’, although the previously announced 25% tariff on non-USMCA compliant goods and 10% on energy and potash have come into effect. Should Canada and Mexico address the US’ concerns over fentanyl, a 12% tariff would be applied to non-USMCA compliant goods. And presumably exporters will rush to increase the share of North American trade that is USMCA compliant.

On the other hand, Asia looks like the biggest loser from the announcement. While new tariffs on China were expected, the announcement of a 34% reciprocal tariff that stacks on top of existing tariffs was higher than anticipated. This pushes the average bilateral tariff rate close to 70%. Other major regional economies, including Japan, South Korea, India and Vietnam now face tariff rates ranging from 24% to 46%. Europe has landed roughly in the lower-middle range, facing 20% tariffs, while the UK appears to be a relative winner, with tariffs of ‘only’ 10%.

Will tariffs go higher still?

There is a meaningful risk that the announcements, as dramatic as they were, do not represent “peak tariffs”. We still think additional sector-specific tariffs are coming, including on semiconductors, copper, lumber and pharmaceuticals. Indeed, these products were mentioned in the executive order, specifying that the reciprocal tariff policy does not apply to them, or indeed to any product currently subject to a Section 232 tariff, including autos, steel and aluminium. The wording appears to leave the door open to the introduction of more specific rates in the future. On the other hand, this does suggest that sector-specific tariffs and reciprocal tariffs aren’t additive. Additionally, the executive order provides the president with the right to modify tariff rates in the event of retaliatory measures, meaning rates on some trade partners could be pushed higher still.

The EU in particular has been clear it intends to push back ‘proportionally’, with trade ministers meeting on 7 April to discuss a response. Canada has also pledged to retaliate.

China’s response may be relatively reserved, but we expect that the authorities will reach for their “retaliation playbook”, curbing exports of critical minerals and pressuring US corporates operating in China, with Tesla a likely target.

A big question remains as to whether the authorities will condone a substantial FX depreciation. The RMB fixing was moved only modestly higher overnight, suggesting a continued desire to lean against depreciation pressure. But the scale of the tariff move could prompt a re-think over time, particularly given China’s tepid inflation.

Alternatively, could tariffs move lower?

There is still scope for US tariffs to eventually settle at a lower level, and this is probably still a widespread expectation. The 10% global baseline is likely a floor, but structuring the reciprocal tariff as an additional rate on top of that at least leaves some chance of it then coming down. Behavioural changes of US consumers may also bring the effective rate down somewhat. And it is possible that a very negative market and voter response may incentivise the Trump administration to temper its policy. However, any de-escalation might be slow, and it is not clear what concessions the administration will seek in exchange for lowering tariffs. With potentially all affected markets seeking to negotiate at once, the US administration may suffer from a lack of bandwidth. Moreover, since the calculation for reciprocal tariffs is based on trade deficits, rather than product-specific tariff rates facing US exporters, the ‘quick win’ of reducing tariffs on US goods may not be good enough. The sector-specific tariffs, as a separate plank of tariff policy, may not be up for negotiation.

And, with higher tariffs being applied almost universally, trade diversion will likely be modest. At a more fundamental level, there is little reason to believe that these measures will succeed in reducing the US trade deficit, which could limit the scope to roll back tariffs under the new framework. Finally, so far, the administration appears far more tolerant of market weakness than in Trump’s first term. Indeed, low bond yields and a weaker dollar may be actively helpful market moves give the administration’s preferences.

Stagflationary economic impacts

The net impact on the US economy will almost certainly be stagflationary, although the magnitude of the price level increase and of the GDP hit are hard to pin down. The shock to growth and inflation is sensitive to whether tariffs are perceived as temporary or permanent, the scope for firms to absorb price rises in their margins, currency moves, and how financial markets react, among other things.

A crude rule-of-thumb is that every 1 percentage point increase in the US weighted average tariff rate translates into a 0.1 percentage point rise in the price level and knocks 0.05-0.1 percent off GDP. This would suggest that the full increase in US tariffs and in recent week could add 2% to the price level and push GDP down by 1-2%.

There is a potential for some offsetting economic benefits if the roughly $0.6 trillion (~2% GDP) that could be raised by the tariffs is used to finance tax cuts rather than deficit reduction. However, once the dynamic impacts of the tariffs are accounted for, which capture the fact that productivity growth is likely to be lower over the long run due to the higher tariffs, then the revenue raised is likely to be much smaller. Some estimates suggest perhaps only half of the $0.6 trillion touted by the administration will end up being raised. Moreover, if the revenue is “used” on tax cuts, it would make negotiating away the tariff increases in the future more difficult.

The Fed faces a difficult trade-off. Policymakers have previously talked about tariffs having only a “transitory” impact on US inflation, but, given the recent sharp increase in inflation expectations, it may be difficult for the Fed to look through this impact.

Date: 3 April 2025

Note: Companies selected for illustrative purposes only to demonstrate the investment management style described herein and not as an investment recommendation or indication of future performance.

Forecast is offered as opinion and is not reflective of potential performance. Forecast is not guaranteed and actual events or results may differ materially.

| This document is strictly for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell, or solicitation of an offer to purchase any security, nor does it constitute investment advice, investment recommendation or an endorsement with respect to any investment products. Investment involves risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and investors may get back less than the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. No liability whatsoever is accepted for any loss arising from any person acting on any information contained in this document. Any data contained herein which is attributed to a third party ("Third Party Data") is the property of (a) third party supplier(s) (the “Owner”) and is licensed for use by Aberdeen**. Third Party Data may not be copied or distributed. Third Party Data is provided “as is” and is not warranted to be accurate, complete or timely. To the extent permitted by applicable law, none of the Owner, Aberdeen** or any other third party (including any third party involved in providing and/or compiling Third Party Data) shall have any liability for Third Party Data or for any use made of Third Party Data. Neither the Owner nor any other third party sponsors, endorses or promotes the fund or product to which Third Party Data relates. **Aberdeen means the relevant member of Aberdeen Group, being Aberdeen Group plc together with its subsidiaries, subsidiary undertakings and associated companies (whether direct or indirect) from time to time. This document is issued by abrdn Hong Kong Limited (“abrdn HK”) and has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission. Copyright © Aberdeen Group plc 2025. All rights reserved. |